CLARKSDALE

Morgan Freeman's Ground Zero Blues Club, New Years Eve, 2004

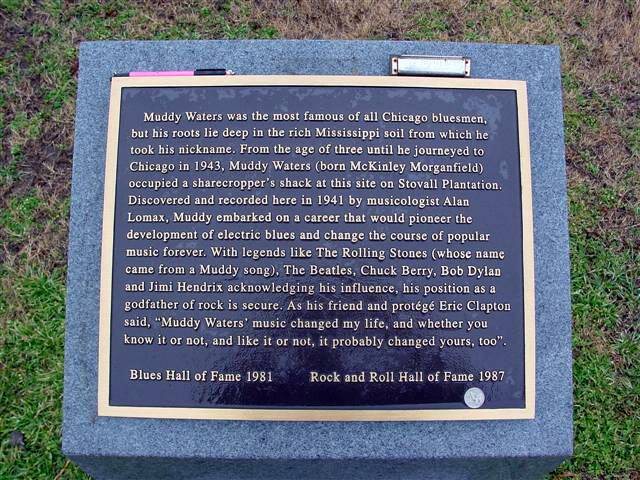

The Delta Blues Museum is located across the street from Ground Zero Blues Club in Clarksdale. It contains many items of interest, including the log structure that occupied the site of Muddy Water's boyhood home shown in the photo at the top of this page. The building itself was the railroad depot at which many bluesmen boarded the train to seek fame and fortune in Chicago and elsewhere.

The Red Top Lounge, also known as Smitty's. At one time, The Jelly Roll Kings, Frank Frost, Sam Carr & Big Jack Johnson, were the house band. The building was on the cover of the King's 1979 album Rockin' the Juke Joint Down with Johnson, Frost and Carr standing out front.

Formerly the G.T. Thomas Afro-American Hospital, the Riverside Hotel is where Bessie Smith, "Empress of the Blues," was pronounced dead following an automobile mishap September 26, 1937. It was converted into a hotel in the 1940s. The Riverside's guest list includes Robert Nighthawk, Sonnyboy Williamson II, Ike Turner and, in 1991, John F. Kennedy, Jr. and his date.

Stackhouse Records/Rooster Blues Building

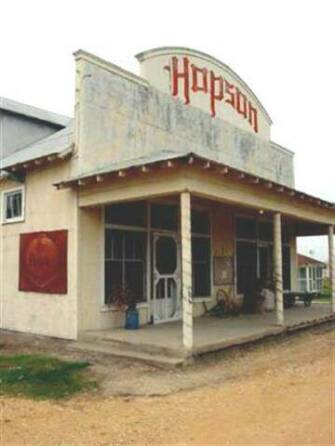

The photographs below were taken at Hopson Plantation, just outside Clarksdale. Several old cotton shacks have been moved from various locations to the plantation grounds where they form a "Delta motel'" named The Shack-up Inn. They have been nicely outfitted in period regalia with a lot of blues flavoring and are quite a fun place to stay.

The old Hopson Plantation Commissary now houses a bar, performance venue, catering facility and a superb and large collection of Delta memorabilia.

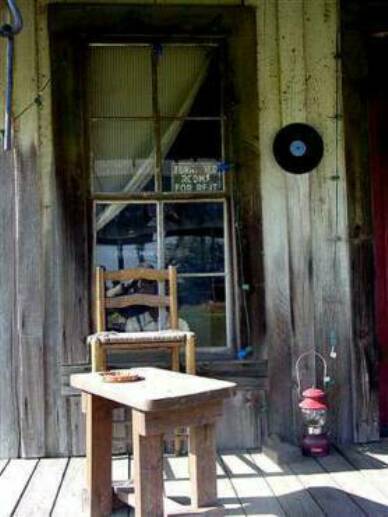

Front porches of a couple of the shacks

Cotton bale on the dock of the gin with the shacks in the background.

Jammin' at Ground Zero

Delta Amusement Cafe is on Delta Avenue, right down the street from Ground Zero (in background, below right) and almost right across the street from the old WROX studios. Be sure to drop by for one of Bobby's delicious meals. Cold beer and the best breakfast in town, I gar-awn-tee.

Music: Muddy Waters, Rock Me

Shack Row

Clarksdale

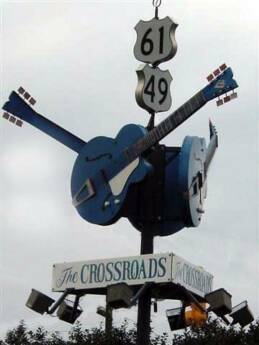

Around the turn of the century, the Illinois Central Railroad and blues highways US 49 and 61 all intersected in Clarksdale, making it one of the richest towns in the Delta. By the 1920s, when Son House learned to play the blues, it was already an important blues town. W. C. Handy, Muddy Waters, John Lee Hooker, Gus Cannnon, Junior Parker and Ike Turner are just a few who were either from Clarksdale or lived there at one time or another. Clarksdale's WROX, one of the nations first blues radio stations kept the blues playing, some recorded right around the corner at Stackhouse Records/Rooster Blues.

This is the site of the cabin in which Muddy Waters (bio near bottom of page) grew up on Stovall Plantation outside Clarksdale.

This image is from the cover of a book I highly recommend, Can't Be Satisfied; The Life and Times of Muddy Waters, by Robert Gordon. See the review on the READING page.

This is Cat Head. Anybody who likes blues is gonna love this place. They have an incredible amount of blues related merchandise that one rarely sees for sale in a retail store. CDs and DVDs galore. Books, magazines, cool blues tee shirts and some outstanding artwork. Cat Head frequently even has live music . I've never been in there when there wasn't someone behind the counter who could answer all my questions about the local blues scene. It's a happenin' place, y'all.

252 Delta Avenue, 662-624-5992. Check it out.

My favorite Delta town.....

Be sure to see the photos of The Shack-Up Inn at the bottom of the page, just below the bios of Muddy Waters, John Lee Hooker and Ike Turner. The Shack-Up Inn is a fun place to stay and an excellent place to throw a party.

Ground Zero photos taken April 2012.

WROX once broadcasted blues across the Delta. Ike Turner used to spin records here and Elvis Presley once played a live broadcast from this studio. These days, they play Classic Soul R&B and broadcast Mississppi State University Bulldog Football on 105.7 FM and 1450 AM.

One can easily imagine bluesmen boarding a bus at this station to seek their fame and fortune.

CLARKSDALE

Sculpture erected at the old intersection of the world's two most famous blues highways United States Highways 61 and 49

Morgan Freeman came in the juke and spent about an hour and a half greeting his admirers, shaking hands, and having his photo taken with people.

Bluesman, Wade Walton's barber shop

Muddy Waters

A postwar Chicago blues scene without the magnificent contributions of Muddy Waters is absolutely unimaginable. From the late '40s on, he eloquently defined the city's aggressive, swaggering, Delta-rooted sound with his declamatory vocals and piercing slide-guitar attack. When he passed away in 1983, the Windy City would never quite recover.

Like many of his contemporaries on the Chicago circuit, Waters was a product of the fertile Mississippi Delta. Born McKinley Morganfield in Rolling Fork, he grew up in nearby Clarksdale on Stovall's Plantation. His idol was the powerful Son House, a Delta patriarch whose flailing slide work and intimidating intensity Waters would emulate in his own fashion.

Musicologist Alan Lomax traveled through Stovall's in August of 1941 under the auspices of the Library of Congress, in search of new talent for purposes of field recording. With the discovery of Morganfield, Lomax must have immediately known he'd stumbled across someone very special.

Setting up his portable recording rig in the Delta bluesman's house, Lomax captured for Library of Congress posterity Waters' mesmerizing rendition of "I Be's Troubled," which became his first big seller when he re-cut it a few years later for the Chess brothers' Aristocrat logo as "I Can't Be Satisfied." Lomax returned the next summer to record his bottleneck-wielding find more extensively, also cutting sides by the Son Simms Four (a string band that Waters belonged to).

Waters was renowned for his blues-playing prowess across the Delta, but that was about it until 1943, when he left for the bright lights of Chicago. A tiff with "the bossman" apparently also had a little something to do with his relocation plans. By the mid-'40s, Waters' slide skills were becoming a recognized entity on Chicago's South side, where he shared a stage or two with pianists Sunnyland Slim and Eddie Boyd, and guitarist Blue Smitty. Producer Lester Melrose, who still had the local recording scene pretty much sewn up in 1946, accompanied Waters into the studio to wax a date for Columbia, but the urban nature of the sides didn't electrify anyone in the label's hierarchy and remained unissued for decades.

Sunnyland Slim played a large role in launching the career of Muddy Waters. The pianist invited him to provide accompaniment for his 1947 Aristocrat session that would produce "Johnson Machine Gun." One obstacle remained beforehand: Waters had a day gig delivering Venetian blinds. But he wasn't about to let such a golden opportunity slip through his talented fingers. He informed his boss that a fictitious cousin had been murdered in an alley, so he needed a little time off to take care of business.

When Sunnyland had finished that auspicious day, Waters sang a pair of numbers, "Little Anna Mae" and "Gypsy Woman," that would become his own Aristocrat debut 78. They were rawer than the Columbia stuff, but not as inexorably down-home as "I Can't Be Satisfied" and its flip, "I Feel Like Going Home" (the latter was his first national R&B hit in 1948). With Big Crawford slapping the bass behind Waters' gruff growl and slashing slide, "I Can't Be Satisfied" was such a local sensation that even Muddy Waters himself had a hard time buying a copy down on Maxwell Street.

He assembled a band that was so tight and vicious on-stage that they were informally known as "the Headhunters"; they'd come into a bar where a band was playing, ask to sit in, and then "cut the heads" of their competitors with their superior musicianship. Little Walter, of course, would single-handily revolutionize the role of the harmonica within the Chicago blues hierarchy; Jimmy Rogers was an utterly dependable second guitarist; and Baby Face Leroy Foster could play both drums and guitar. On top of their instrumental skills, all four men could sing powerfully.

1951 found Waters climbing the R&B charts no less than four times, beginning with "Louisiana Blues," and continuing through "Long Distance Call," "Honey Bee," and "Still a Fool." Although it didn't chart, his 1950 classic "Rollin' Stone" provided a certain young British combo with a rather enduring name. Leonard Chess himself provided the incredibly unsubtle bass-drum bombs on Waters' 1952 smash "She Moves Me."

"Mad Love," his only chart bow in 1953, is noteworthy as the first hit to feature the rolling piano of Otis Spann, who would anchor the Waters aggregation for the next 16 years. By this time, Foster was long gone from the band, but Rogers remained, and Chess insisted that Walter -- by then a popular act in his own right -- make nearly every Waters session into 1958 (why break up a winning combination?). There was one downside to having such a peerless band; as the ensemble work got tighter and more urbanized, Waters' trademark slide guitar was largely absent on many of his Chess waxings.

Willie Dixon was playing an increasingly important role in Muddy Waters' success. In addition to slapping his upright bass on Waters' platters, the burly Dixon was writing one future bedrock standard after another for him: "I'm Your Hoochie Coochie Man," "Just Make Love to Me," and "I'm Ready"; seminal performances all, and each blasted to the uppermost reaches of the R&B lists in 1954.

When labelmate Bo Diddley borrowed Waters' swaggering beat for his strutting "I'm a Man" in 1955, Waters turned around and did him tit-for-tat by reworking the tune ever so slightly as "Mannish Boy" and enjoying his own hit. "Sugar Sweet," a pile-driving rocker with Spann's 88s anchoring the proceedings, also did well that year. 1956 brought three more R&B smashes: "Trouble No More," "Forty Days & Forty Nights," and "Don't Go No Farther."

But rock & roll was quickly blunting the momentum of veteran blues aces like Waters; Chess was growing more attuned to the modern sounds of Chuck Berry, Bo Diddley, the Moonglows, and the Flamingos. Ironically, it was Muddy Waters that had sent Berry to Chess in the first place.

After that, there was only one more chart item, 1958's typically uncompromising (and metaphorically loaded) "Close to You." But Waters' Chess output was still of uniformly stellar quality, boasting gems like "Walking Thru the Park" (as close as he was likely to come to mining a rock & roll groove) and "She's Nineteen Years Old," among the first sides to feature James Cotton's harp instead of Walter's, in 1958. That was also the year that Muddy Waters and Spann made their first sojourn to England, where his electrified guitar horrified sedate Britishers accustomed to the folksy homilies of Big Bill Broonzy. Perhaps chagrined by the response, Waters paid tribute to Broonzy with a solid LP of his material in 1959.

Cotton was apparently the bandmember that first turned Muddy on to "Got My Mojo Working," originally cut by Ann Cole in New York. Waters' 1956 cover was pleasing enough but went nowhere on the charts. But, when the band launched into a supercharged version of the same tune at the 1960 Newport Jazz Festival, Cotton and Spann put an entirely new groove to it, making it an instant classic (fortuitously, Chess was on hand to capture the festivities on tape).

As the 1960s dawned, Muddy Waters' Chess sides were sounding a trifle tired. Oh, the novelty thumper "Tiger in Your Tank" packed a reasonably high-octane wallop, but his adaptation of Junior Wells' "Messin' With the Kid" (as "Messin' With the Man") and a less-than-timely "Muddy Waters Twist" were a long way removed indeed from the mesmerizing Delta sizzle that Waters had purveyed a decade earlier.

Overdubbing his vocal over an instrumental track by guitarist Earl Hooker, Waters laid down an uncompromising "You Shook Me" in 1962 that was a step in the right direction. Drummer Casey Jones supplied some intriguing percussive effects on another 1962 workout, "You Need Love," which Led Zeppelin liked so much that they purloined it as their own creation later on.

In the wake of the folk-blues boom, Waters reverted to an acoustic format for a fine 1964 LP, Folk Singer, that found him receiving superb backing from guitarist Buddy Guy, Dixon on bass, and drummer Clifton James. In October, he ventured overseas again as part of the Lippmann- and Rau-promoted American Folk Blues Festival, sharing the bill with Sonny Boy Williamson, Memphis Slim, Big Joe Williams, and Lonnie Johnson.

The personnel of the Waters band was much more fluid during the 1960s, but he always whipped them into first-rate shape. Guitarists Pee Wee Madison, Luther "Snake Boy" Johnson, and Sammy Lawhorn; harpists Mojo Buford and George Smith; bassists Jimmy Lee Morris and Calvin "Fuzz" Jones; and drummers Francis Clay and Willie "Big Eyes" Smith (along with Spann, of course) all passed through the ranks.

In 1964, Waters cut a two-sided gem for Chess, "The Same Thing"/"You Can't Lose What You Never Had," that boasted a distinct 1950s feel in its sparse, reflexive approach. Most of his subsequent Chess catalog, though, is fairly forgettable. Worst of all were two horrific attempts to make him a psychedelic icon. 1968's Electric Mud forced Waters to ape his pupils via an unintentionally hilarious cover of the Stones' "Let's Spend the Night Together" (session guitarist Phil Upchurch still cringes at the mere mention of this album). After the Rain was no improvement the following year.

Partially salvaging this barren period in his discography was the Fathers and Sons project, also done in 1969 for Chess, which paired Muddy Waters and Spann with local youngbloods Paul Butterfield and Mike Bloomfield in a multi-generational celebration of legitimate Chicago blues.

After a period of steady touring worldwide but little standout recording activity, Waters' studio fortunes were resuscitated by another of his legion of disciples, guitarist Johnny Winter. Signed to Blue Sky, a Columbia subsidiary, Waters found himself during the making of the first LP, Hard Again; backed by pianist Pinetop Perkins, drummer Willie Smith, and guitarist Bob Margolin from his touring band; Cotton on harp; and Winter's slam-bang guitar, Waters roared like a lion who had just awoken from a long nap.

Three subsequent Blue Sky albums continued the heartwarming back-to-the basics campaign. In 1980, his entire combo split to form the Legendary Blues Band; needless to note, he didn't have much trouble assembling another one (new members included pianist Lovie Lee, guitarist John Primer, and harpist Mojo Buford).

By the time of his death in 1983, Muddy Waters' exalted place in the history of blues (and 20th-century popular music, for that matter) was eternally assured. The Chicago blues genre that he turned upside down during the years following World War II would never recover; and that's a debt we'll never be able to repay.

~ Bill Dahl, All Music Guide

Ike Turner dies in San Diego at age 76

By ELLIOT SPAGAT, Associated Press Writer

SAN DIEGO - Ike Turner, whose role as one of rock's critical architects was overshadowed by his ogrelike image as the man who brutally abused former wife Tina Turner, died Wednesday at his home in suburban San Diego. He was 76.

Turner died at his San Marcos home, Scott M. Hanover of Thrill Entertainment Group, which managed Turner's career, told The Associated Press.

There was no immediate word on the cause of death, which was first reported by celebrity Web site TMZ.com.

Turner managed to rehabilitate his image somewhat in later years, touring around the globe with his band the Kings of Rhythm and drawing critical acclaim for his work. He won a Grammy in 2007 in the traditional blues album category for "Risin' With the Blues."

But his image is forever identified as the drug-addicted, wife-abusing husband of Tina Turner. He was hauntingly portrayed by Laurence Fishburne in the movie "What's Love Got To Do With It," based on Tina Turner's autobiography.

In a 2001 interview with The Associated Press, Turner denied his ex-wife's claims of abuse and expressed frustration that he had been demonized in the media while his historic role in rock's beginnings had been ignored.

"You can go ask Snoop Dogg or Eminem, you can ask the Rolling Stones or (Eric) Clapton, or you can ask anybody — anybody, they all know my contribution to music, but it hasn't been in print about what I've done or what I've contributed until now," he said.

Turner, a member of the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, is credited by many rock historians with making the first rock 'n' roll record, "Rocket 88," in 1951. Produced by the legendary Sam Phillips, it was groundbreaking for its use of distorted electric guitar.

But as would be the case for most of his career, Turner, a prolific session guitarist and piano player, was not the star on the record — it was recorded with Turner's band but credited to singer Jackie Brenston.

And it would be another singer — a young woman named Anna Mae Bullock — who would bring Turner his greatest fame, and infamy.

Turner met the 18-year-old Bullock, whom he would later marry, in 1959 and quickly made the husky-voiced woman the lead singer of his group, refashioning her into the sexy Tina Turner. Her stage persona was highlighted by short skirts and stiletto heels that made her legs her most visible asset. But despite the glamorous image, she still sang with the grit and fervor of a rock singer with a twist of soul.

The pair would have two sons. They also produced a string of hits. The first, "A Fool In Love," was a top R&B song in 1959, and others followed, including "I Idolize You" and "It's Gonna Work Out Fine."

But over the years their genre-defying sound would make them favorites on the rock 'n' roll scene, as they opened for acts like the Rolling Stones.

Their densely layered hit "River Deep, Mountain High" was one of producer Phil Spector's proudest creations. A rousing version of "Proud Mary," a cover of the Creedence Clearwater Revival hit, became their signature song and won them a Grammy for best R&B vocal performance by a group.

Still, their hits were often sporadic, and while their public life depicted a powerful, dynamic duo, Tina Turner would later charge that her husband was an overbearing wife abuser and cocaine addict.

In her 1987 autobiography, "I, Tina," she narrated a harrowing tale of abuse, including suffering a broken nose. She said that cycle ended after a vicious fight between the pair in the back seat of a car in Las Vegas, where they were scheduled to perform.

It was the only time she ever fought back against her husband, Turner said.

After the two broke up, both fell into obscurity and endured money woes for years before Tina Turner made a dramatic comeback in 1982 with the release of the album "Private Dancer," a multiplatinum success with hits such as "Let's Stay Together" and "What's Love Got To Do With It."

The movie based on her life, "What's Love Got To Do With It," was also a hit, earning Angela Bassett an Oscar nomination.

But Fishburne's glowering depiction of Ike Turner also furthered Turner's reputation as a rock villain.

Meanwhile, Turner never again had the success he enjoyed with his former wife.

After years of drug abuse, he was jailed in 1989 and served 17 months.

Turner told the AP he originally began using drugs to stay awake and handle the rigors of nonstop touring during his glory years.

"My experience, man, with drugs — I can't say that I'm proud that I did drugs, but I'm glad I'm still alive to convey how I came through," he said. "I'm a good example that you can go to the bottom. ... I used to pray, `God, if you let me get three days clean, I will never look back.' But I never did get to three days. You know why? Because I would lie to myself. And then only when I went to jail, man, did I get those three days. And man, I haven't looked back since then."

But while he would readily admit to drug abuse, Turner always denied abusing his ex-wife.

After years out of the spotlight his career finally began to revive in 2001 when he released the album "Here and Now." The recording won rave reviews and a Grammy nomination and finally helped shift some of the public's attention away from his troubled past and onto his musical legacy.

"His last chapter in life shouldn't be drug abuse and the problems he had with Tina," said Rob Johnson, the producer of "Here and Now."

Turner spent his later years making more music and touring, even while he battled emphysema.

Robbie Montgomery — one of the "Ikettes," backup singers who worked with Ike and Tina Turner — said Turner's death was "devastating" to her.

"He gave me my start. He gave a million people their start," Montgomery said.

Accolades for Turner's early and later work continued to come in as he grew older, and the once-broke musician managed to garner a comfortable income as his songs were sampled by a variety of rap acts.

In interviews toward the end of his life, Turner would acknowledge having made many mistakes, but maintained he was still able to carry himself with pride.

"I know what I am in my heart. And I know regardless of what I've done, good and bad, it took it all to make me what I am today," he once told the AP.

John Lee Hooker

He was beloved worldwide as the king of the endless boogie, a genuine blues superstar whose droning, hypnotic one-chord grooves were at once both ultra-primitive and timeless. But John Lee Hooker recorded in a great many more styles than that over a career that stretched across more than half a century.

"The Hook" was a Mississippi native who became the top gent on the Detroit blues circuit in the years following World War II. The seeds for his eerily mournful guitar sound were planted by his stepfather, Will Moore, while Hooker was in his teens. Hooker had been singing spirituals before that, but the blues took hold and simply wouldn't let go. Overnight visitors left their mark on the youth, too: legends like Blind Lemon Jefferson, Charley Patton, and Blind Blake, who all knew Moore.

Hooker heard Memphis calling while he was still in his teens, but he couldn't gain much of a foothold there. So he relocated to Cincinnati for a seven-year stretch before making the big move to the Motor City in 1943. Jobs were plentiful, but Hooker drifted away from day gigs in favor of playing his unique free-form brand of blues. A burgeoning club scene along Hastings Street didn't hurt his chances any.

In 1948, the aspiring bluesman hooked up with entrepreneur Bernie Besman, who helped him hammer out his solo debut sides, "Sally Mae" and its seminal flip, "Boogie Chillen." This was blues as primitive as anything then on the market; Hooker's dark, ruminative vocals were backed only by his own ringing, heavily amplified guitar and insistently pounding foot. Their efforts were quickly rewarded. Los Angeles-based Modern Records issued the sides and "Boogie Chillen" — a colorful, unique travelogue of Detroit's blues scene — made an improbable jaunt to the very peak of the R&B charts.

Modern released several more major hits by "the Boogie Man" after that: "Hobo Blues" and its raw-as-an-open wound flip, "Hoogie Boogie"; "Crawling King Snake Blues" (all three 1949 smashes); and the unusual 1951 chart-topper "I'm in the Mood," where Hooker overdubbed his voice three times in a crude early attempt at multi-tracking.

But Hooker never, ever let something as meaningless as a contract stop him for making recordings for other labels. His early catalog is stretched across a road map of diskeries so complex that it's nearly impossible to fully comprehend (a vast array of recording aliases don't make things any easier).

Along with Modern, Hooker recorded for King (as the geographically challenged Texas Slim), Regent (as Delta John, a far more accurate handle), Savoy (as the wonderfully surreal Birmingham Sam & His Magic Guitar), Danceland (as the downright delicious Little Pork Chops), Staff (as Johnny Williams), Sensation (for whom he scored a national hit in 1950 with "Huckle Up, Baby"), Gotham, Regal, Swing Time, Federal, Gone (as John Lee Booker), Chess, Acorn (as the Boogie Man), Chance, DeLuxe (as Johnny Lee), JVB, Chart, and Specialty; before finally settling down at Vee-Jay in 1955 under his own name. Hooker became the point man for the growing Detroit blues scene during this incredibly prolific period, recruiting guitarist Eddie Kirkland as his frequent duet partner while still recording for Modern.

Once tied in with Vee-Jay, the rough-and-tumble sound of Hooker's solo and duet waxings was adapted to a band format. Hooker had recorded with various combos along the way before, but never with sidemen as versatile and sympathetic as guitarist Eddie Taylor and harpist Jimmy Reed, who backed him at his initial Vee-Jay date that produced "Time Is Marching" and the superfluous sequel "Mambo Chillun."

Taylor stuck around for a 1956 session that elicited two genuine Hooker classics, "Baby Lee" and "Dimples," and he was still deftly anchoring the rhythm section (Hooker's sense of timing was his and his alone, demanding big-eared sidemen) when the Boogie Man finally made it back to the R&B charts in 1958 with "I Love You Honey."

Vee-Jay presented Hooker in quite an array of settings during the early '60s. His grinding, tough blues "No Shoes" proved a surprisingly sizable hit in 1960, while the storming "Boom Boom," his top seller for the firm in 1962 (it even cracked the pop airwaves), was an infectious R&B dance number benefiting from the reported presence of some of Motown's house musicians. But there were also acoustic outings aimed squarely at the blossoming folk-blues crowd, as well as some attempts at up-to-date R&B that featured highly intrusive female background vocals (allegedly by the Vandellas) and utterly unyielding structures that hemmed Hooker in unmercifully.

British blues bands such as the Animals and Yardbirds idolized Hooker during the early '60s; Eric Burdon's boys cut a credible 1964 cover of "Boom Boom" that outsold Hooker's original on the American pop charts. Hooker visited Europe in 1962 under the auspices of the first American Folk Blues Festival, leaving behind the popular waxings "Let's Make It" and "Shake It Baby" for foreign consumption.

Back home, Hooker cranked out gems for Vee-Jay through 1964 ("Big Legs, Tight Skirt," one of his last offerings on the logo, was also one of his best), before undergoing another extended round of label-hopping (except this time, he was waxing whole LPs instead of scattered 78s). Verve-Folkways, Impulse, Chess, and BluesWay all enticed him into recording for them in 1965-1966 alone! His reputation among hip rock cognoscenti in the States and abroad was growing exponentially, especially after he teamed up with blues-rockers Canned Heat for the massively selling album Hooker 'n' Heat in 1970.

Eventually, though, the endless boogie formula grew incredibly stagnant. Much of Hooker's 1970s output found him laying back while plodding rock-rooted rhythm sections assumed much of the work load. A cameo in the 1980 movie The Blues Brothers was welcome, if far too short.

But Hooker wasn't through; not by a long shot. With the expert help of slide guitarist extraordinaire/producer Roy Rogers, the Hook waxed The Healer, an album that marked the first of his guest star-loaded albums (Carlos Santana, Bonnie Raitt, and Robert Cray were among the luminaries to cameo on the disc, which picked up a Grammy).

Major labels were just beginning to take notice of the growing demand for blues records, and Pointblank snapped Hooker up, releasing Mr. Lucky (this time teaming Hooker with everyone from Albert Collins and John Hammond to Van Morrison and Keith Richards). Once again, Hooker was resting on his laurels by allowing his guests to wrest much of the spotlight away from him on his own album, but by then, he'd earned it. Another Pointblank set, Boom Boom, soon followed.

Happily, Hooker enjoyed the good life throughout the '90s. He spent much of his time in semi-retirement, splitting his relaxation time between several houses acquired up and down the California coast. When the right offer came along, though, he took it, including an amusing TV commercial for Pepsi. He also kept recording, releasing such star-studded efforts as 1995's Chill Out and 1997's Don't Look Back. All this helped him retain his status as a living legend, and he remained an American musical icon; and his stature wasn't diminished upon his death from natural causes on June 21, 2001.

~ Bill Dahl, All Music Guide

Ground Zero photos below taken January, 2016

Catfish, bacon, lettuce & tomato sandwich and fried dill pickles.

Red's, 398 Sunflower Ave, a current Clarksdale juke and live blues venue.

Across the street from Ground Zero, looking north up Delta Ave past The Delta Amusement Cafe on the right at the portico

Double click here to add text.

Almost the same shot I took in daylight in April, 2012

January 2016

Heavy Suga' & The SweeTones:

~~~

Heather Cross, bass/vocals

~

Jerry Jines, guitar/vocals

~

Greg Batterson

(not pictured), harmonica/trumpet/vocals

~

Lee Williams, drums/vocals